Before we can effectively help clients explore their family patterns, we must first understand our own. This principle takes on particular importance when it comes to bias—the assumptions, prejudices, and attitudes we absorb from our families of origin that inevitably influence our clinical work.

As Halevy (1998, p. 233) argues, "In order to become competent and ethical practitioners, students must understand themselves and how they see others." The "Genogram with an Attitude," a specialized adaptation developed for multicultural counseling training, offers a structured approach for exploring how bias has been transmitted across generations in our own families.

This article examines how genograms can serve as tools for therapist self-awareness, helping practitioners recognize and address the biases they bring to their clinical work.

The Problem of Unexamined Bias

Why Self-Awareness Matters

Every therapist enters the consulting room carrying assumptions—about family, about normalcy, about health and pathology. These assumptions are not personal failings; they are the inevitable product of growing up within particular families, communities, and cultural contexts. However, unexamined assumptions become problematic when they interfere with our ability to understand and help clients whose experiences differ from our own.

Biases related to race, gender, class, sexual orientation, religion, ethnicity, ability, and other dimensions of identity can affect:

- Which client behaviors we perceive as problematic versus normal

- How we interpret family dynamics and relationships

- What goals we implicitly assume therapy should achieve

- Which clients we feel comfortable or uncomfortable working with

- How power dynamics operate in the therapeutic relationship

The Intergenerational Transmission of Bias

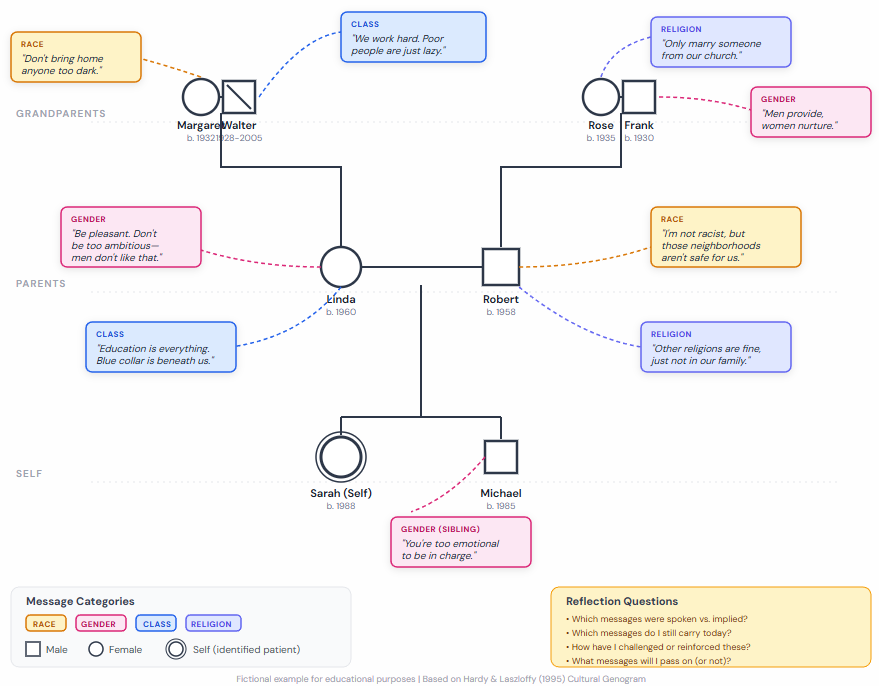

Just as families transmit patterns of communication, coping, and relationship across generations, they also transmit attitudes. Halevy (1998, p. 236) observes that "the genogram is an extremely useful tool that traces not only the transmission of culture but also the transmission of attitudes."

Understanding this intergenerational process serves an important function: it helps separate personal blame from systemic responsibility. When practitioners recognize that they "come by their biases honestly" through family transmission, they can address these patterns without excessive guilt or defensiveness (Halevy, 1998, p. 236).

The "Genogram with an Attitude"

Origins and Purpose

Halevy (1998) developed the "Genogram with an Attitude" as a training exercise for marriage and family therapy students in a multicultural counseling course. Building on Hardy and Laszloffy's (1995) cultural genogram, this adaptation specifically focuses on tracing the transmission of prejudice and bias through family systems.

The exercise operates from several key premises:

- Attitudes about race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and other identity dimensions are transmitted through families across generations

- Individual prejudices exist within broader sociopolitical and historical contexts

- Understanding how bias was transmitted can create space for taking responsibility without excessive personal blame

- Collective examination in a supportive context helps reduce shame as a barrier to change

The Process

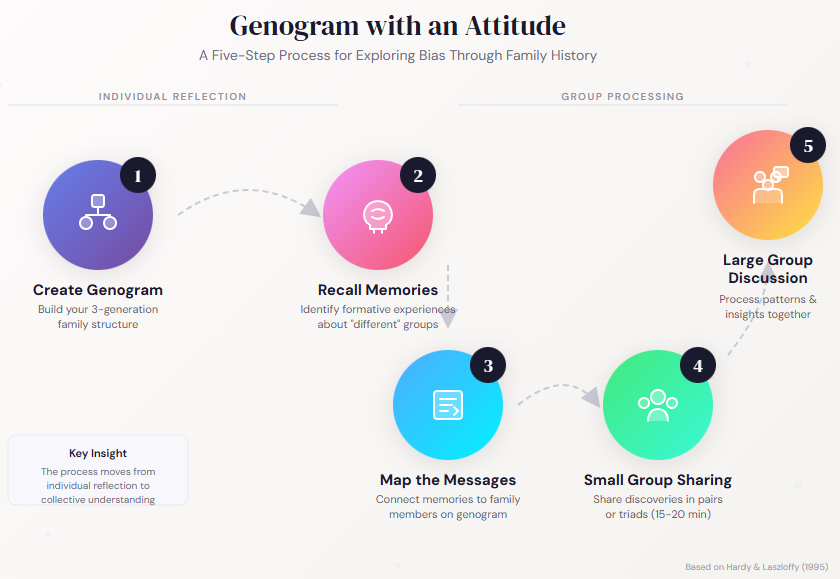

Halevy (1998) describes a structured process that can be adapted for various training contexts:

Step 1: Create the Genogram Structure

Begin by outlining a traditional genogram including all family members across three to four generations. This provides the foundation for the bias exploration that follows.

Step 2: Recall Formative Memories

Recall specific memories where race, gender, class, sexual orientation, religion, ethnicity, ability, appearance, or age were focal points. For each memory, identify:

- Who was present

- What occurred

- How you felt

- What messages you received (explicit or implicit)

Step 3: Map the Messages

Write the areas of prejudice and specific messages next to the corresponding family members on the genogram. This visual mapping reveals patterns of transmission across generations.

Step 4: Share in Small Groups

Present the genogram to a small group of trusted colleagues (Halevy recommends triads with approximately 20 minutes per person). The small group format creates safety for vulnerable sharing.

Step 5: Large Group Discussion

After small group presentations, gather for collective discussion of common themes. This collective sharing helps participants recognize they are not alone in carrying inherited biases.

What Practitioners Discover

Common Themes

Through this process, practitioners typically discover:

- Universality of bias: Prejudices exist in all families, though the specific content varies

- Generational patterns: Attitudes often trace back multiple generations

- Mixed messages: Families may transmit contradictory messages about the same groups

- Unspoken rules: Much bias transmission occurs through what is not said as much as what is said

- Contextual influences: Family attitudes reflect the historical and social contexts in which they developed

From Shame to Responsibility

A crucial outcome of the exercise is movement from shame and guilt toward responsibility. When practitioners recognize how bias was transmitted through their family system, they can address these patterns without excessive personal blame (Halevy, 1998).

This distinction matters: while practitioners did not create the social contexts that shaped their family's attitudes, they bear responsibility for how they respond to these inherited patterns in their own lives and clinical work.

Impact on Clinical Practice

Halevy (1998) reports that students who complete this exercise describe significant changes in their clinical work. They become better able to:

- Recognize when personal attitudes are interfering with patient treatment

- Approach clients from different backgrounds with greater openness

- Examine their assumptions before pathologizing unfamiliar family patterns

- Discuss issues of bias with clients when clinically relevant

- Take responsibility for ongoing self-examination and growth

Implementing Self-Awareness Practices

For Individual Practitioners

Even without a formal training context, practitioners can adapt this approach for personal self-examination:

- Create your own bias genogram: Map the messages about various identity groups you received from different family members

- Identify sources and patterns: Notice which attitudes came from which family members and how they connect across generations

- Examine current impact: Reflect honestly on how these early messages still influence your perceptions and clinical work

- Seek consultation: Discuss your findings with trusted colleagues or supervisors who can offer outside perspectives

- Commit to ongoing work: Self-awareness is not a one-time achievement but an ongoing practice

For Training Programs

Training programs can integrate this approach through:

- Dedicated multicultural counseling courses

- Supervision groups focused on self-awareness

- Professional development workshops

- Peer consultation formats

The small group format Halevy describes—with its emphasis on safety, shared vulnerability, and collective reflection—appears essential to the exercise's effectiveness.

Creating Safety

Any exploration of personal bias requires psychological safety. Key elements include:

- Clear confidentiality agreements

- Voluntary participation in sharing

- Skilled facilitation

- Emphasis on learning rather than judgment

- Recognition that everyone carries inherited biases

- Focus on responsibility rather than blame

Connecting to Broader Practice

Integration with Cultural Genograms

The "Genogram with an Attitude" works well in conjunction with Hardy and Laszloffy's (1995) cultural genogram. While the cultural genogram explores pride and shame related to cultural heritage, the bias-focused genogram specifically examines attitudes toward other groups. Together, these exercises provide a more complete picture of how identity and attitudes have been shaped by family and cultural context.

Implications for Client Work

Self-awareness about bias directly improves client care. Practitioners who have examined their own inherited attitudes are better equipped to:

- Create genuinely welcoming spaces for diverse clients

- Avoid imposing culturally-specific assumptions as universal norms

- Recognize their own reactions as potential sources of clinical information

- Address issues of power and privilege when relevant to treatment

- Model the kind of honest self-examination they may invite from clients

Conclusion

The genogram is often thought of as a tool for understanding clients. Equally important is its capacity to help practitioners understand themselves. By tracing how bias has been transmitted across generations in our own families, we can bring greater awareness to the assumptions we carry into clinical work.

Halevy's "Genogram with an Attitude" offers a structured approach to this self-examination—one that acknowledges the universality of inherited bias while creating space for taking responsibility without excessive shame.

"When students look to their familial generations before them, they find evidence that they come by their biases 'honestly.' When they share this information with each other, they discover that their families share the process of bias—that is, that prejudices are found in all families." — Halevy (1998, p. 236)

This recognition is not an endpoint but a beginning. The ongoing work of self-awareness—examining our assumptions, seeking feedback, and remaining open to growth—is essential to ethical, effective practice across all the dimensions of difference we encounter in our clinical work.

Create Your Own Genogram

Create professional multigenerational family diagrams with our intuitive web-based tool. Document relationships, health conditions, and family patterns.

Start FreeReferences

Amorin-Woods, D. (2024). Genograms, culture, love and sisterhood: A conversation with Monica McGoldrick. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 45(3), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1602

Halevy, J. (1998). A genogram with an attitude. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 24(2), 233–242.

Hardy, K. V., & Laszloffy, T. A. (1995). The cultural genogram: Key to training culturally competent family therapists. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 21(3), 227–237.

McGoldrick, M., Gerson, R., & Petry, S. (2008). Genograms: Assessment and intervention (3rd ed.). W. W. Norton.