When Monica McGoldrick first traveled to Ireland in 1975, something shifted in her understanding of family therapy. As she later reflected, "From the day I landed in Ireland, I never stopped asking people, 'What's your story?', 'What's your cultural background?', 'How do people in your family do it?' It became so totally obvious that culture plays a huge role" (Amorin-Woods, 2024, p. 360).

This insight would prove transformative for the field. McGoldrick's subsequent work integrating cultural perspectives into genogram practice created what Amorin-Woods (2024, p. 351) describes as "a major paradigm shift in practice and research." For more on the history of genograms and McGoldrick's contributions, see our companion article. Today, culturally informed assessment is recognized as essential to effective family therapy—yet many practitioners still struggle to move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach.

This article explores how cultural context shapes family systems and offers guidance for integrating cultural awareness into genogram-based assessment.

Why Culture Matters in Family Assessment

The Limits of Universal Models

Early family systems theory, developed primarily by Murray Bowen, focused on what were presumed to be universal emotional processes common to all families. While Bowen's concepts—differentiation, triangulation, multigenerational transmission—remain valuable, critics have noted their limitations when applied across cultural contexts.

As Amorin-Woods (2024, p. 357) observes, "The concept of differentiation was developed in the context of white, middle-class families, so its use and applicability is rather limiting." In collectivist cultures where family interdependence is valued over individual autonomy, high levels of what Western theory might label "enmeshment" may actually reflect culturally appropriate connection.

Culture Shapes Everything

Cultural background influences virtually every aspect of family life that genograms seek to capture:

- Family structure: Who counts as "family"? Extended kin, godparents, close family friends?

- Communication patterns: Is direct confrontation acceptable or taboo? Who speaks to whom about what?

- Gender roles: How are responsibilities and power distributed between men and women?

- Intergenerational relationships: What obligations exist between generations? Who cares for elders?

- Response to crisis: How do families cope with illness, death, or other stressors?

- Expression of emotion: What feelings are acceptable to express? How are they shown?

Without cultural context, practitioners risk misinterpreting family patterns that are normative within a given cultural framework as pathological.

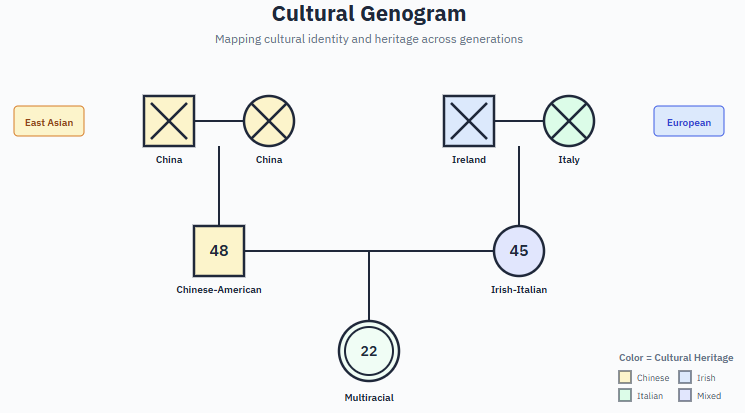

The Cultural Genogram

Origins and Purpose

Hardy and Laszloffy (1995) developed the cultural genogram specifically to help practitioners explore their own cultural identity and its influence on clinical work. While traditional genograms map family structure and relationships, the cultural genogram adds explicit attention to ethnic heritage, cultural traditions, and the intersection of culture with family patterns.

Butler (2008) lists the cultural genogram among significant adaptations that have expanded genogram practice beyond its original scope. Unlike the standard genogram's focus on biological and legal relationships, the cultural genogram invites exploration of:

- Pride and shame associated with cultural heritage

- Cultural norms and values transmitted across generations

- Experiences of discrimination or marginalization

- Acculturation patterns and intergenerational cultural conflicts

- Spiritual and religious traditions

Key Questions for Cultural Exploration

McGoldrick's approach emphasizes curiosity about cultural patterns. She describes asking clients (Amorin-Woods, 2024, p. 360):

- "What's your story?"

- "What's your cultural background?"

- "How do people in your family do it?"

- "How do they eat in your family?"

- "How did they talk in your family?"

- "How did they argue in your family?"

These seemingly simple questions open pathways to understanding how culture has shaped family interaction patterns across generations.

Expanding the Definition of Family

Beyond Blood and Legal Ties

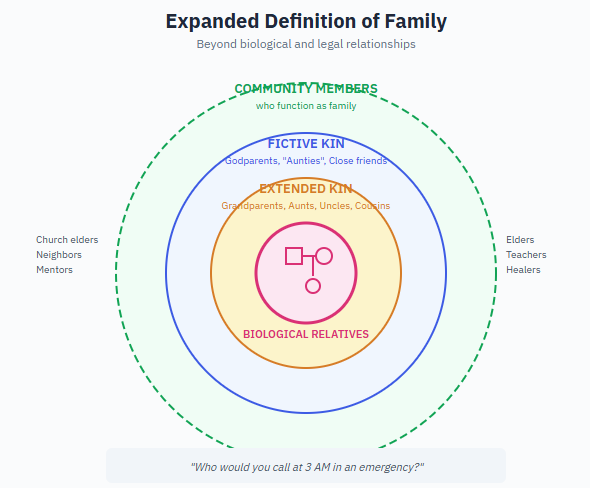

A significant contribution of culturally informed practice is recognizing that "family" itself is a cultural construct. Connolly (2005, p. 82) observes that "our rapidly changing culture redefines and stretches society's concept of 'family.' While the definition of family can differ from person to person... a single definition of family has been rendered obsolete by current realities."

Traditional genograms, with their focus on biological and legal relationships, may inadvertently marginalize:

- Extended kin networks important in many cultures

- Fictive kin (godparents, "aunties," chosen family)

- Community members who function as family

- Non-traditional family structures

As Connolly (2005, p. 100) warns, focusing only on biological relatives risks "mapping an inaccurate family system" that misses relationships central to the client's actual support network and identity.

The Self-Created Genogram

Connolly's (2005) self-created genogram offers one approach to this challenge. Rather than beginning with prescribed symbols and structures, practitioners invite clients to "represent your family in whatever way you would like." This open-ended approach:

- Centers the client as expert on their own family

- Removes assumptions about who belongs in the family picture

- Allows creative, authentic expression of family experience

- Reveals relationships that traditional methods might overlook

This approach may be particularly valuable when working across cultural differences, as it allows the client's cultural framework to guide the assessment rather than imposing the practitioner's assumptions.

Practical Applications

Preparing for Culturally Informed Assessment

Before conducting genogram-based assessment with clients from diverse backgrounds, practitioners should:

- Examine their own cultural lens: What assumptions do you carry about "normal" family structure and function?

- Research relevant cultural contexts: While avoiding stereotypes, develop basic knowledge of cultural patterns relevant to your client population.

- Adopt a stance of cultural humility: Approach each family as unique rather than assuming cultural background determines their experience.

- Ask, don't assume: Use curious, open-ended questions to learn how culture operates in this particular family.

During the Assessment

When creating genograms with clients from diverse cultural backgrounds:

- Expand the family boundary: Ask who the client considers family, including non-biological relationships

- Explore cultural context: Inquire about cultural traditions, immigration history, experiences of discrimination

- Attend to cultural strengths: Identify cultural resources and protective factors, not just problems

- Watch for cultural conflicts: Note intergenerational tensions around acculturation or cultural values

- Remain curious about meaning: The same pattern may have different significance across cultures

Interpreting Through a Cultural Lens

When analyzing genogram information:

- Consider whether patterns that appear problematic might be culturally normative

- Identify cultural resources that could support therapeutic goals

- Attend to the impact of discrimination, marginalization, or historical trauma

- Recognize that family roles and expectations vary across cultures

- Avoid imposing Western individualistic values on collectivist family systems

Challenges and Considerations

Avoiding Stereotypes

Cultural awareness should not become cultural stereotyping. Within any cultural group, tremendous individual variation exists. Practitioners must balance cultural knowledge with attention to each family's unique experience.

Addressing Power and Privilege

Culturally informed practice requires attention to power dynamics—both within families and in the therapeutic relationship. How do cultural differences between practitioner and client affect the assessment process? Whose cultural framework is privileged?

Navigating Cultural Conflicts

Families often contain cultural conflicts—between generations with different acculturation levels, between spouses from different backgrounds, or between family values and the dominant culture. Genograms can help map these tensions and their origins.

Conclusion

Culture is not an add-on to family assessment—it is fundamental to understanding how families function. As McGoldrick's career-long work demonstrates, integrating cultural awareness into genogram practice reveals patterns and resources that would otherwise remain invisible.

The cultural lens reminds practitioners that families exist within cultural contexts that shape their structures, communication patterns, values, and ways of coping with challenge. By approaching each family with cultural humility and genuine curiosity, practitioners can create assessments that honor the family's own understanding of who they are and how they work.

"We're all in it together. Those who came before are influencing us even as we speak, and we are influencing what's going to come after as we speak." — Monica McGoldrick (Amorin-Woods, 2024, p. 363)

Understanding how culture shapes this multigenerational influence is essential to effective family-focused work.

Create Your Own Genogram

Create professional multigenerational family diagrams with our intuitive web-based tool. Document relationships, health conditions, and family patterns.

Start FreeReferences

Amorin-Woods, D. (2024). Genograms, culture, love and sisterhood: A conversation with Monica McGoldrick. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 45(3), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1602

Butler, J. F. (2008). The family diagram and genogram: Comparisons and contrasts. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(3), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180701291055

Connolly, C. M. (2005). Discovering "family" creatively: The self-created genogram. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 1(1), 81–105. https://doi.org/10.1300/J456v01n01_07

Hardy, K. V., & Laszloffy, T. A. (1995). The cultural genogram: Key to training culturally competent family therapists. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 21(3), 227–237.

McGoldrick, M., Gerson, R., & Petry, S. (2008). Genograms: Assessment and intervention (3rd ed.). W. W. Norton.