The genogram has become one of the most widely used assessment tools in family therapy, social work, nursing, and mental health practice. Yet few practitioners know the fascinating history behind this visual mapping technique—or that the term "genogram" itself remains something of a mystery even to its pioneers.

"I don't know where genograms came from to tell you the truth, and neither did Murray. We did try to find out unsuccessfully." — Monica McGoldrick (Amorin-Woods, 2024, p. 357)

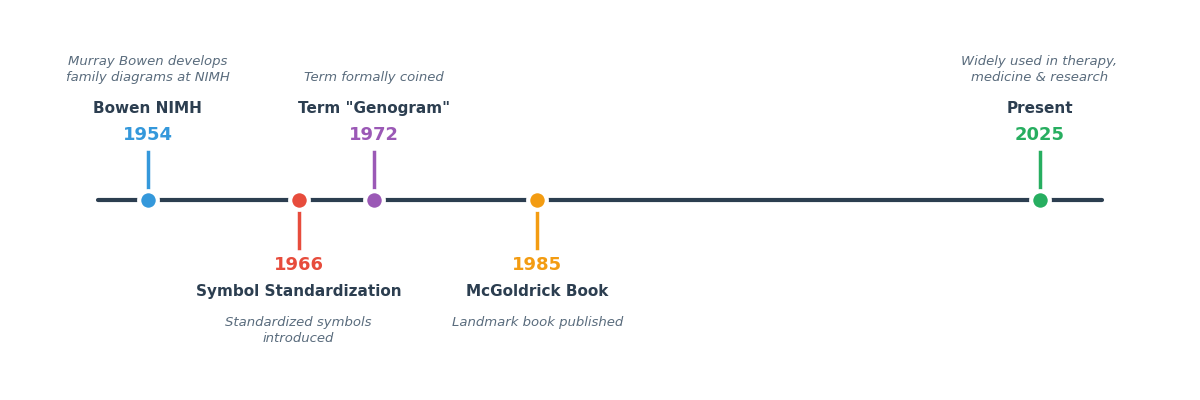

This article traces the development of genograms from their origins in Murray Bowen's research at the National Institutes of Mental Health through their popularization in the 1980s and their continued evolution today. Understanding this history helps practitioners appreciate both the theoretical foundations and practical applications of this essential clinical tool.

The Origins: Murray Bowen and Family Diagrams (1954-1966)

The NIMH Research Project

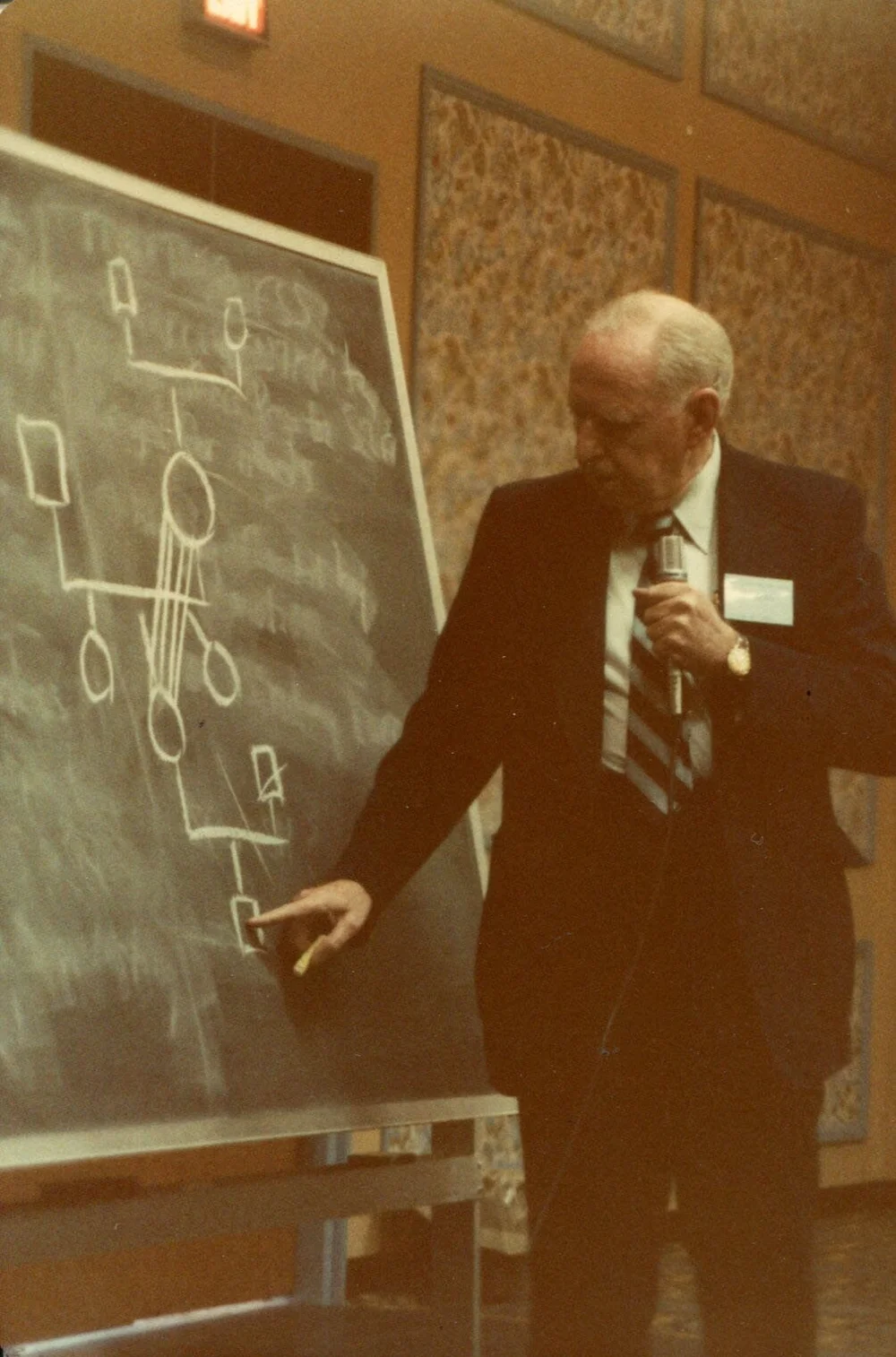

Photo: Andrea Schara / The Bowen Center for the Study of the Family

The roots of the genogram can be traced to psychiatrist Murray Bowen's groundbreaking research at the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) from 1954 to 1959. During this period, Bowen began developing what he called "family diagrams" as part of his emerging family systems theory (Butler, 2008).

By 1957, "the tool for diagramming families is in place and being used by the investigators" (Dysinger, 2003, as cited in Butler, 2008, p. 172). Bowen's choice of terminology was deliberate—he preferred the straightforward descriptive term "family diagram" rather than coining a new word (Kerr & Bowen, 1988).

Theoretical Foundations

Central to Bowen's approach was his conceptualization of the family as a unified emotional system rather than simply a group of separate individuals (Puskar & Nerone, 1996). His family systems theory, developed between 1966 and 1970, identified eight core concepts that remain foundational to genogram interpretation today:

- Differentiation of self

- Triangles

- Nuclear family emotional process

- Family projection process

- Multigenerational transmission process

- Sibling position

- Emotional cutoff

- Societal emotional process

The family diagram served as a visual tool to record what Butler (2008, p. 170) describes as the "facts of functioning" across at least three generations, reflecting emotional processes within the family system.

Symbol Standardization

In 1966, Bowen established the symbols commonly applied for family diagrams, creating a standardized visual language for representing family structure, relationships, and patterns (Piasecka et al., 2018). These symbols—squares for males, circles for females, horizontal lines for marriages, vertical lines for children—formed the foundation that practitioners still use today. For a comprehensive overview of these symbols, see our complete guide to genogram symbols.

The Emergence of the Term "Genogram" (1972)

A New Name Takes Hold

While Bowen continued to use "family diagram," a new term emerged from his students. Philip J. Guerin, who had trained under Bowen, appears to have originated the term "genogram" in the late 1960s or early 1970s (Butler, 2008). Guerin later directed the Center for Family Learning in Westchester, New York (Amorin-Woods, 2024).

The word first appeared in published literature in 1972, when Guerin and Fogarty defined a genogram as "a schematic diagram of the three-generational family relationship system" (Guerin & Fogarty, 1972, as cited in Piasecka et al., 2018, p. 1).

As McGoldrick recalled, "Murray didn't want to call them genograms for some reason; he called them 'family diagrams'. His 'descendants', the people who work directly at his Institute, followed the Bowen rules" (Amorin-Woods, 2024, p. 357).

An Important Distinction

It is essential to recognize that family diagrams and genograms, while related, represent distinctly different assessment methods with different theoretical foundations (Butler, 2008). The family diagram remains grounded in Bowen's natural systems theory with its focus on universal biological and emotional processes. The genogram, as it evolved, came to represent a broader family systems perspective that emphasizes multiple contextual levels including culture, community, and society.

"It is without question that the genogram is derived directly from Bowen's family diagram." — Butler (2008, p. 176)

Popularization and Expansion (1980s-2000s)

The McGoldrick and Gerson Contribution

Photo: Multicultural Family Institute

The genogram achieved widespread recognition and standardization largely through the work of Monica McGoldrick and Randy Gerson (Piasecka et al., 2018). Their 1985 book, Genograms in Family Assessment, provided the first comprehensive practical guide for clinical application.

McGoldrick's contribution extended beyond mere popularization. She was "pivotal in expanding the use of genograms by acknowledging the important elements of culture, ethnicity, race and gender. This novel lens created a major paradigm shift in practice and research" (Amorin-Woods, 2024, p. 351).

This cultural lens emerged from McGoldrick's personal experience. As she described it: "From the day I landed in Ireland, I never stopped asking people, 'What's your story?', 'What's your cultural background?', 'How do people in your family do it?' It became so totally obvious that culture plays a huge role" (Amorin-Woods, 2024, p. 360).

Standardization Efforts

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, various professional groups worked to standardize genogram symbols and methodology. The Task Force of the North American Primary Care Research Group established recommended symbol standards (Puskar & Nerone, 1996), while McGoldrick and colleagues continued refining their approach through subsequent editions of their seminal text.

By 1999, McGoldrick, Gerson, and Shellenberger had published an updated edition that Butler (2008, p. 175) describes as the "gold standard" for genogram clinical application, including symbols for diverse family configurations, relationship patterns, and individual characteristics.

The Genogram Today

Widespread Adoption Across Disciplines

What began as a family therapy tool has expanded far beyond its origins. Genograms are now used across multiple disciplines including mental health, social work, nursing, genetic research, education, and even business contexts (Joseph et al., 2023).

In nursing practice, genograms have become "an indispensable tool for nurses of any specialty in their work with the patient" (Piasecka et al., 2018, p. 4). The tool enables assessment of physical and psychosocial health across three generations, supporting a comprehensive and holistic approach to patient care.

Specialized Adaptations

The basic genogram has spawned numerous specialized variations to address specific clinical needs:

- Cultural Genogram (Hardy & Laszloffy, 1995) — exploring ethnic and cultural identity

- Spiritual Genogram (Wiggins-Frame, 2000) — examining religious and spiritual dynamics

- Transgenerational Trauma and Resilience Genogram (Goodman, 2013) — addressing trauma transmission across generations

- Time-line Genogram (Friedman et al., 1988) — highlighting temporal aspects of family relationships

- Sexual Genogram (Hof & Berman, 1986) — exploring sexual attitudes and patterns

From Paper to Digital

The evolution from hand-drawn diagrams to digital tools represents the latest chapter in genogram history. While Butler (2008) noted that no computer software existed for producing family diagrams at that time, various genogram software programs have since emerged.

However, as recently as 2018, researchers observed that comprehensive software enabling creation, archiving, and research use of genograms remained lacking: "Unfortunately, there is no available software enabling the creation of genograms which would make it possible to record information and archive it for research and treatment purposes" (Piasecka et al., 2018, p. 2).

This gap in available tools continues to drive innovation in the field, with modern web-based applications like WebGeno working to address these limitations.

The Ongoing Research Gap

Despite decades of clinical use, empirical research on genogram effectiveness remains limited. A 2023 systematic review found "a scarcity of empirical research on the therapeutic effectiveness of genograms in family therapy in the international context" (Joseph et al., 2023, p. 23).

Joseph et al. (2023) note that most published literature consists of case studies and descriptive articles rather than controlled intervention studies. The majority of research has focused on practitioner perspectives, with limited exploration of client experiences with genogram-based interventions.

This research gap presents both a challenge and an opportunity for the field. As genograms continue to evolve and digital tools make them more accessible, rigorous research into their therapeutic effectiveness becomes increasingly important.

Conclusion

From Murray Bowen's hand-drawn family diagrams at the NIMH in the 1950s to today's digital genogram applications, this visual assessment tool has undergone remarkable evolution. The contributions of pioneers like Bowen, Guerin, McGoldrick, and Gerson transformed a clinical research tool into an essential component of family-focused practice across multiple disciplines.

Understanding this history helps practitioners appreciate the theoretical depth underlying what might appear to be a simple family tree. Whether called a family diagram or a genogram, this tool continues to serve its original purpose: making visible the patterns, relationships, and processes that shape family systems across generations.

"We're all in it together. Those who came before are influencing us even as we speak, and we are influencing what's going to come after as we speak." — Monica McGoldrick (Amorin-Woods, 2024, p. 363)

Create Your Own Genogram

Experience the evolution of genogram tools firsthand. WebGeno provides a modern, web-based platform for creating professional genograms.

Start FreeReferences

Amorin-Woods, D. (2024). Genograms, culture, love and sisterhood: A conversation with Monica McGoldrick. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 45(3), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1602

Butler, J. F. (2008). The family diagram and genogram: Comparisons and contrasts. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(3), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180701291055

Goodman, R. D. (2013). The transgenerational trauma and resilience genogram. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 26(3-4), 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2013.820172

Joseph, B., Dickenson, S., McCall, A., & Roga, E. (2023). Exploring the therapeutic effectiveness of genograms in family therapy: A literature review. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 31(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807221104133

Kerr, M. E., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. W. W. Norton.

McGoldrick, M., & Gerson, R. (1985). Genograms in family assessment. Norton.

McGoldrick, M., Gerson, R., & Shellenberger, S. (1999). Genograms: Assessment and intervention (2nd ed.). Norton.

Piasecka, K., Slusarska, B., & Drop, B. (2018). Genograms in nursing education and practice: A sensitive but very effective technique: A systematic review. Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education, 8(6), 640. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0711.1000640

Puskar, K., & Nerone, M. (1996). Genogram: A useful tool for nurse practitioners. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 3, 55–60.