A genogram is more than a family tree—it is a visual language that communicates family structure, relationships, and health patterns across generations. To read and create effective genograms, practitioners must understand the standardized symbols that form this language.

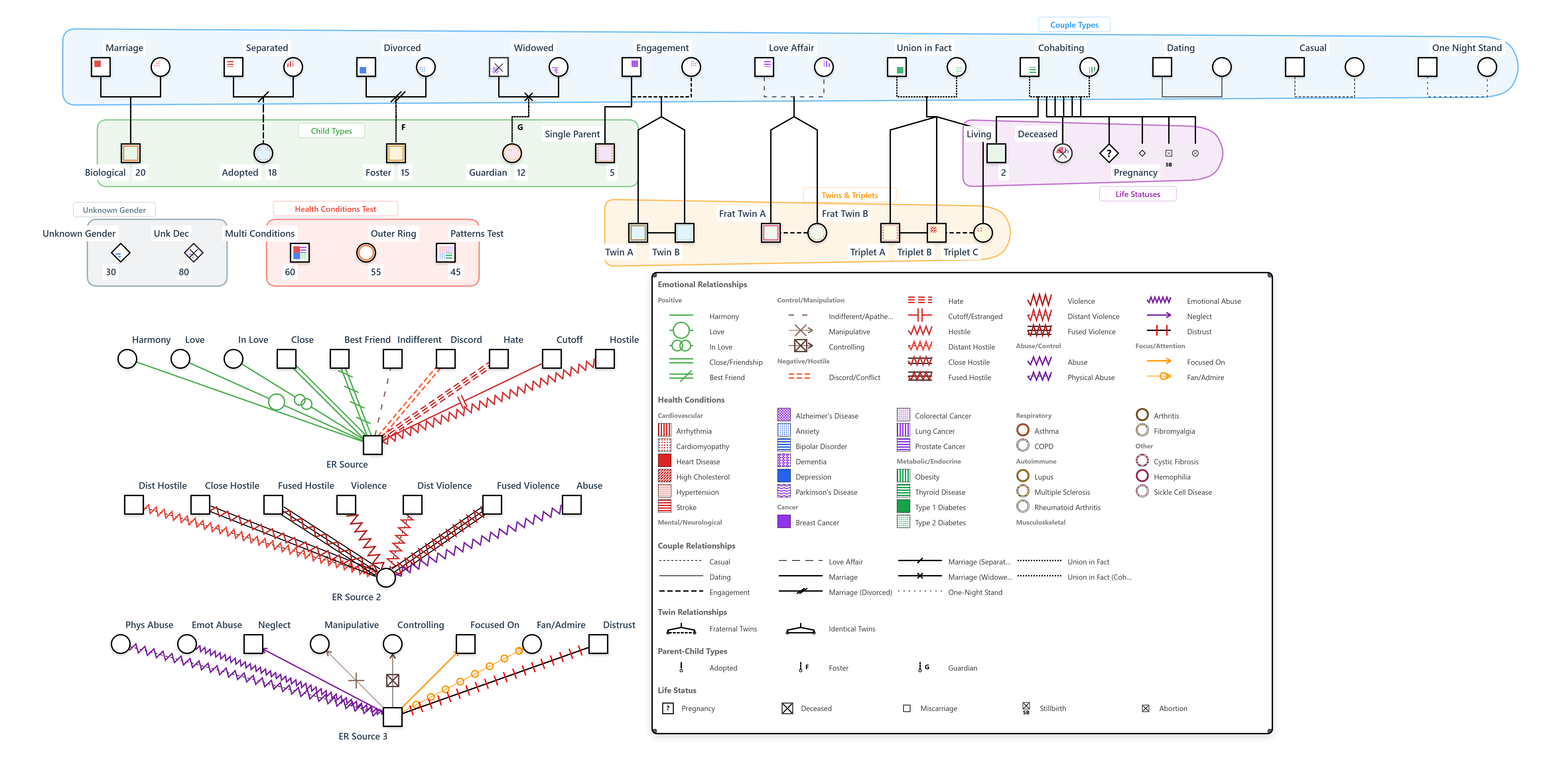

Murray Bowen established the foundational symbols for family diagrams in 1966, creating what Piasecka et al. (2018) describe as a standardized visual system for representing family information. Since then, the symbol set has expanded significantly. According to their systematic review, contemporary genogram practice uses approximately 100 distinct symbols organized into three main categories: structural symbols depicting family members, line symbols representing relationships, and graphic symbols indicating health conditions and life circumstances.

Structural Symbols: Representing Family Members

The most fundamental genogram symbols represent individual family members. These symbols convey basic demographic information at a glance.

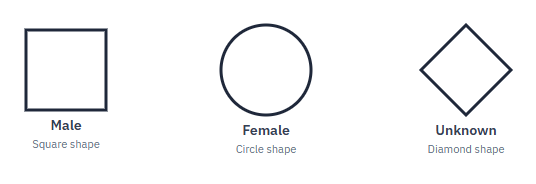

Gender Symbols

The core gender symbols have remained consistent since Bowen's original system:

- Square: Male

- Circle: Female

- Diamond or Question Mark: Gender unknown or unspecified

Age and Status Indicators

Additional information can be incorporated into or around these basic shapes:

- Age: Written inside the symbol or below it

- Name: Written below or beside the symbol

- Deceased: An "X" through the symbol, with death date noted

- Identified patient/client: Double border around the symbol

- Pregnancy: Small triangle or circle within the mother's symbol

- Miscarriage: Small filled circle or triangle with an "X"

- Stillbirth: Symbol with an "X" and "SB" notation

Birth Order and Placement

According to standard conventions, children are arranged from left to right in order of birth, with the oldest on the left (Piasecka et al., 2018). Butler (2008) notes that in Bowen's original family diagram format, males were placed on the left and females on the right of couple pairings.

Relationship Lines: Mapping Family Connections

Relationship lines connect individual symbols to show how family members relate to one another. These lines represent both legal/biological relationships and emotional patterns.

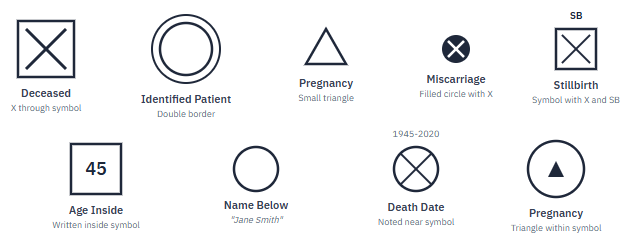

Couple Relationships

Horizontal lines connect partners and indicate their relationship status:

- Marriage: Single solid horizontal line

- Cohabitation/Living together: Single solid line, sometimes marked "LT" (Butler, 2008)

- Engagement: Single solid line with notation

- Separation: Single line with one diagonal slash

- Divorce: Single line with two diagonal slashes

- Multiple marriages: Shown sequentially, with most recent typically on the outer edge

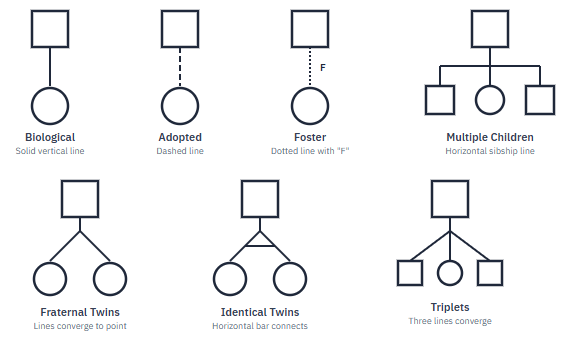

Parent-Child Connections

Vertical lines connect parents to children:

- Biological child: Solid vertical line from the couple line to the child

- Adopted child: Dotted or dashed vertical line, or solid line with brackets

- Foster child: Dotted line with "F" notation

- Twins: Two vertical lines converging to a single point on the couple line

- Identical twins: Twins connected by a horizontal bar

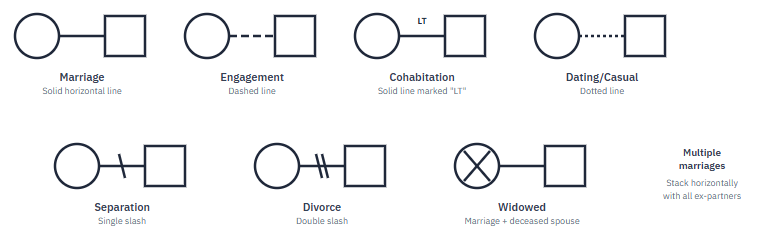

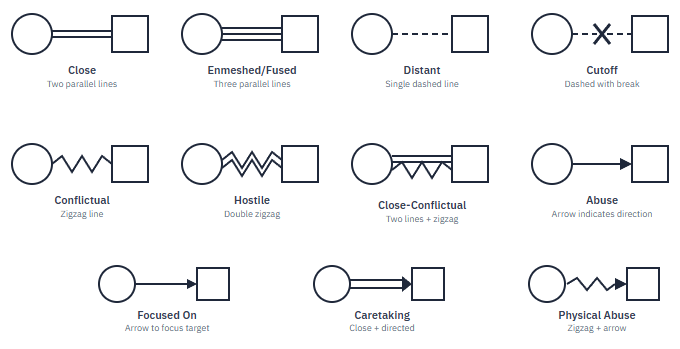

Emotional Relationship Patterns

Beyond structural connections, genograms can depict the quality and nature of relationships between family members. McGoldrick and colleagues developed an extensive system of relationship lines that Butler (2008, p. 175) describes as the "gold standard" for genogram practice.

Common Relationship Patterns

- Close/Harmonious: Two parallel lines

- Very close/Enmeshed: Three parallel lines

- Distant: Single dotted line

- Estranged/Cut off: Line with break or perpendicular marks

- Conflictual: Zigzag or wavy line

- Close and conflictual: Combination of parallel and zigzag lines

- Focused on: Arrow pointing toward the focus of attention

- Abusive: Zigzag with specific notation

These relationship indicators help practitioners visualize emotional patterns that may span multiple generations, supporting assessment of what Bowen termed the "multigenerational transmission process" (Puskar & Nerone, 1996).

Health and Social Condition Symbols

One of the most clinically useful aspects of genograms is their capacity to track health conditions, mental health issues, and social circumstances across generations. Piasecka et al. (2018) identified 61 graphic symbols for diseases, disabilities, and disorders in their systematic review.

Standard Approaches from the Literature

The traditional method for representing health conditions involves filling or marking the individual's symbol:

- Filled/shaded symbol: Indicates presence of a condition

- Half-filled symbol: Carrier status or partial condition

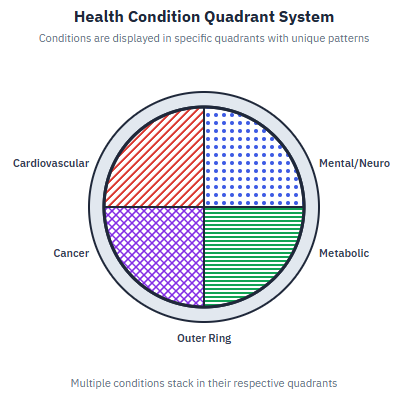

- Quadrant system: McGoldrick et al. (2008) describe dividing the symbol into sections to represent different condition categories (e.g., cardiovascular, mental health, cancer, metabolic)

However, as Piasecka et al. (2018) note, there is "incomplete symbol standardization" for health conditions across the literature. Different practitioners and software tools implement varying approaches to this challenge.

WebGeno's Pattern-Based Implementation

WebGeno addresses the standardization challenge by implementing a pattern-based system that builds on the quadrant concept from the literature while adding visual differentiation:

- Four inner quadrants: Cardiovascular (top-left), Mental/Neurological (top-right), Cancer (bottom-left), Metabolic/Endocrine (bottom-right)

- Outer ring: Additional categories including Respiratory, Autoimmune, Musculoskeletal, and Other conditions

- Distinct patterns: Each category uses a unique visual pattern (diagonal stripes, dots, crosshatch, horizontal lines, etc.) to aid quick identification

This WebGeno-specific implementation supports 42 pre-defined health conditions across 8 categories, with the ability to add custom conditions as needed.

Common Condition Categories

Regardless of the specific notation system used, practitioners commonly track:

- Cardiovascular conditions: Heart disease, hypertension, stroke

- Mental health: Depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia

- Substance use: Alcohol abuse, drug addiction

- Cancer: Breast, colon, lung, and other malignancies

- Metabolic disorders: Diabetes, thyroid conditions

- Neurological conditions: Dementia, Parkinson's disease

Specialized Symbol Systems

As genogram practice has evolved, practitioners have developed specialized symbol sets for specific clinical contexts.

Variations by Theoretical Approach

Butler (2008) documents numerous specialized genogram types, each with adapted symbols:

- Cultural Genogram (Hardy & Laszloffy, 1995): Incorporates cultural identity markers

- Spiritual Genogram (Wiggins-Frame, 2000): Religious affiliation and spiritual practices

- Sexual Genogram (Hof & Berman, 1986): Attitudes and patterns related to sexuality

- Time-line Genogram (Friedman et al., 1988): Temporal sequencing of events

Best Practices for Using Symbols

Consistency and Clarity

Whatever symbol system you use, consistency is essential. Piasecka et al. (2018) note that incomplete symbol standardization remains a challenge. To maintain clarity:

- Use a legend to define any symbols that might be ambiguous

- Follow established conventions (McGoldrick et al. remains the primary reference)

- Apply the same symbols consistently throughout a single genogram

Practical Considerations

- Keep it readable: Avoid overcrowding with too many symbols

- Use color strategically: Color can differentiate condition categories but ensure accessibility

- Date your genogram: Family situations change; dating helps track evolution

- Include a key: Especially important when sharing genograms across disciplines

Conclusion

Genogram symbols provide practitioners with a powerful visual vocabulary for documenting family patterns across generations. From basic structural symbols established by Bowen in the 1960s to contemporary additions for health conditions and relationship patterns, this system enables efficient communication of information that would otherwise require extensive narrative description.

Mastering these symbols allows practitioners to create genograms that serve multiple purposes: clinical assessment, treatment planning, client education, and professional communication. For practitioners new to genograms, beginning with the fundamental structural and relationship symbols provides a solid foundation. As familiarity grows, incorporating health condition tracking and specialized symbol systems can enhance the clinical utility of this essential assessment tool.

References

Butler, J. F. (2008). The family diagram and genogram: Comparisons and contrasts. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(3), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180701291055

McGoldrick, M., Gerson, R., & Petry, S. (2008). Genograms: Assessment and intervention (3rd ed.). W. W. Norton.

Piasecka, K., Slusarska, B., & Drop, B. (2018). Genograms in nursing education and practice: A sensitive but very effective technique: A systematic review. Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education, 8(6), 640. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0711.1000640

Puskar, K., & Nerone, M. (1996). Genogram: A useful tool for nurse practitioners. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 3, 55–60.

Create Professional Genograms with WebGeno

WebGeno includes all standard genogram symbols with an intuitive interface. Build clear, professional family diagrams in minutes.

Try WebGeno Free